by Holger Slowik (18.01.2021)

translation by Edward Lee (10.11.2022)

While the word 'archive' rarely inspires joy, the opposite can be said of the "Joy of Music (Schott Archives)" series, which Schott produced for its 250th birthday. There are five volumes containing mostly virtuosic, sometimes meditative, but always entertaining treasures from the publishing house's archive. It’s an exciting insight into the music culture of the 19th century!

The word 'archive' does not usually evoke many positive associations: dark basements or low attics, crammed full of dusty files, occupied mainly by scientists and officials administering the past. But archives don't deserve such a bad reputation! The documents stored in archives keep the past alive: every time you browse through an archive, it is like embarking upon an adventure back through time.

At home, regular mucking out may make very good sense, and the mindset of not being able to bring oneself to throw anything away can be fatal - in the case of institutions such as music publishers however, such an attitude would ultimately lead to a betrayal of history: if only works that found their way into, and remained in the repertoire today were preserved, we would have no idea of the musical environment in which the composers we value today grew up and lived. Quite apart from the fact that many composers who were highly regarded during their lifetime, but then fell into obscurity, deserve the chance to be put to the test and – in the best case – rediscovered.

Schott Music, which celebrated its 250th birthday together with Ludwig van Beethoven in 2020, boasts one of the most extensive archives of its kind. Luckily, the many generations of Schott employees throughout the years threw almost nothing away! This publishing archive, which is so important for music history, was taken over by the state libraries of Berlin and Munich in 2014, and has since been scientifically processed, and made digitally accessible to the public.

In view of the publisher’s anniversary, the current Schott generation combed through their extensive archive, and from a wealth of 24,377 pieces, made an exciting selection of works published by Schott in the 19th century. The result is five anthologies, one for piano solo and one each for violin, violoncello, flute and clarinet with piano accompaniment. Each volume contains about a dozen compositions. The motto of the publisher’s anniversary, 'Joy of Music', also became the title of the anniversary publication. Firstly, Joy is the title of what is probably the most famous first edition published by Schott: Beethoven’s 9th Symphony with the final chorus on Schiller's Ode to Joy. And secondly, the selected works are intended to convey one thing above all: the joy of music.

Of course, it’s not always that easy to find this joy: some of the works here are highly virtuosic. Amateurs who want to explore these volumes need to have mastered their instrument to an advanced level; Music students however will find a treasure trove of performance pieces and encores here. Judging all the works on a scale of 1-5, some pieces equal to a medium difficulty of level 3 can be found in all volumes, although most are closer to levels 4 and 5.

The five volumes contain works by 63 different composers, and unfortunately only two female composers. Only two composers, Charles Gounod and Julius Schulhoff appear in more than one volume. The selection is varied and individually tailored to each respective instrument. Around ten of the 63 composers have more or less found their place within the core repertoire. Thankfully, however, it is not their most famous works which appear, rather their lesser-known pieces. There is either a specific reference to Schott's publishing history, as with Beethoven's first publication with the Mainz publishers, his Righini-Variations for piano, or they are works presented in new, contemporary arrangements, like Haydn's Adagio from Symphony No. 24, arranged for flute and piano, or Chopin's Mazurka op. 17/1, arranged for violin and piano.

The majority of the composers featured are only slightly known today, or are known in a different context, and form an exciting cross-section of musical life in the 19th century. Musicians such as Gottlieb Heinrich Köhler and Caspar Kummer, both of whose works feature in the flute volume, went through the traditional Stadtpfeiffer training, to serve the town as a musician for civil occasions, and were versatile musicians who also composed. Köhler, for example, was not only a flautist, but also a violinist and percussionist in the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. Some were also instrument makers who made a significant contribution to the further development of their instruments, such as the flautist Theobald Böhm or the pianist Henri Herz. Others, on the other hand, were important music teachers and are still known today for their school works and etude collections, such as the clarinettist Carl Baermann and of course Carl Czerny, whose etudes have tormented generations of piano students. However, if you know his romantic nocturne for piano, Le Désir, it is hard to disagree with Igor Stravinsky, who admired Czerny as a "bloody minded musician". Finally, there are also works by the most famous virtuoso soloists of their time, who wrote pieces to perform themselves, such as pianist Sigismund Thalberg, who, on his American tour, surprised audiences with performances of his variations on the folk song Home! Sweet Home!.

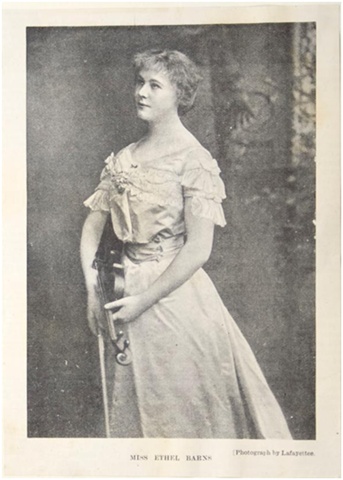

The "notes on individual pieces" found in each volume compile a great deal of information about each work and author into a small space. If you read them all in one go, you will be amazed at the variety of biographies and the width and breadth of musical experience. You gain insights into teacher-pupil relationships and musician networks of the 19th century, and it’s hard not to marvel as musical life of the era gradually begins to become more international. Xavier Boisselot, for example, whose Bolero appears in the flute volume, studied and worked in Paris, and then worked in London, and enjoyed the twilight of his career as a conductor in Shanghai. The fact that Schott also opened their first branch in London in 1835 can be seen in the collection: the two composers Ethel Barns and Ethel Harraden presented in the cello volume were highly respected members of the London music scene. Despite all the wealth of international artists, the pianist Louis Moreau Gottschalk really sticks out. The life of this composer of Le Banjo. Esquisse américaine for piano was pure adventure: he was born in New Orleans and educated in Paris, he went on to tour the civil war-torn USA with two grand pianos on a specially equipped train, and finally fled to South America because of an affair, where he died of malaria at the age of forty.

Speaking of Le Banjo: alongside many characterful pieces and variations, and particularly in popular opera melodies, the volumes contain many works which show the growing fascination in central Europe for everything exotic in the 19th century. For example, this is very clear in La Paloma by Sebastián de Yradier, An Arabic Lamentation by Jenö Hubay and Allegro alla Spagnuola by Giulio Briccialdi. This also included enthusiasm for the exotic closer to home. The 19th century opened up the Alps not only for tourism, but also for music. Joseph Küffner's Alpenlied and Carl Baermann's Ein Abend auf den Bergen, both for clarinet, are good examples. The latter work, with the stations of a mountain hike written in the notes, represents a chamber music forerunner of Richard Strauss's Alpensinfonie. An extra special delicacy, that is almost unplayable at the suggested tempo, is the piano etude Le Chemin de Fer by Charles-Valentin Alkan, probably the earliest example of the small but fine genre of railway music.

The individual volumes follow the musical text of the first editions, a detailed critical report is not available and also not necessary. Misprints in the original editions have been corrected. At one point, a massive mistake was finally made right after 150 years. In the first edition of Giulio Briccialdi's Allegro alla Spagnuola for flute and piano, 20 bars were simply forgotten and left out in the middle of the piece. The Schott team were able to reconstruct the missing bars from existing archive material. This in itself is also part of music publishing history.

Incidentally, fans of the original scores can also find what they are looking for in the Schott Archive series. The Mainz publishing house has been making its archive treasures accessible as reprints of the historical editions for some time.

With the five volumes in the Joy of Music series, Schott Music has given itself and all of us a fantastic birthday present, which goes well beyond the anniversary year, and in which there is so much to discover. We are transported back to the musical salons of the 19th century, when there was still no strict separation between light entertaining and 'serious' classical music. When the concept of the untouchable work of art was still unknown and works by great composers were often heard in arrangements and shortened versions. There was still no music preserved as recordings, anyone who wanted to hear the Magic Flute or Carmen either went to the opera house, or made music arrangements of the works themselves.

The Joy of Music series brings this paramount joy of music, in music and of music making into the 21st century.